Half a Heart Away

I left Nepal ten days sooner than I meant to. With a shocked heart and a belly tied down with dimenhydrinate, I sat in the front seat of a grey sumo. Eleven of our bodies jolted up and down, left and right, as our coachman navigated the switchbacks leading northeast to Kathmandu. Below my sunglasses, I saw the driver looking at my hand squeezing the door handle. He had just unified our right tires with the edge of a cliff after passing a truck carrying two buffalo. Momentum alone can be a savior. I didn't like this car at all; the dashboard was clean and the rearview mirror was unimpeded. Where were the plastic marigolds surrounding a bobble-headed Ganesh as he watched over our travel? Where was the battered picture of Shiva to block what was behind us? Even some lucky dice or a rabbit foot would be better than this. I eased myself by framing the elephant-headed god in my mind. I said a little prayer and accepted my death, just in case I needed to.

I thought about where I had been just a few days ago. Up in the forest south of the river, the laboratory technician had placed a bunch of red flowers behind her ear and posed against a tree. She wanted photos from my iPhone camera to post on her social media page. Sushila Gurung reminded me that this was the national flower of Nepal. We all posed in a circle on the hill and took a group selfie with handfuls of the lali guras while the clinic dogs wrestled around us. I was urged to taste a flower; told that it was delicious.

My mother loved these flowers. After my dad got out of the military and we settled into a suburban neighborhood, she planted them in many colors all over our property. She also told us not to eat them because they are poisonous. I'd researched this in 2017, after participating in a blossom hunt in this same wooded area behind the Bajrabarahi temple. The juice from the Rhododendron arboreum flower contains some potent medicine. It reduces blood sugar by promoting the secretion of insulin and the breakdown of glucose.1 It also appears to significantly lower our blood pressure and heart rate. Unfortunately, it is so good at doing this that it can become fatal.2 The gardener who taught my mom that these magenta clusters were toxic was correct. Yet, with the high rates of hypertension and diabetes here and back in the US, I couldn’t help but wonder to myself: at what dose? In a country with limited resources, the thought of harvesting these abundant flowers could be appealing, if only they were safe.

I came here to teach our three Nepali healthcare providers. The goal was to help them with an increased awareness of the non-communicable diseases we are addressing through our Healthy Lifestyle Center model. I knew I had limited time and could only cover a small amount of material. I decided to focus my efforts on cardiovascular disease. Perhaps this was because I also committed to this trip to heal my own heart, which I felt was breaking over the last three years.

I see our hearts symbolized by a ruby-colored flower like this one. Just like a flower, our hearts bloom with their fullest expression during the late spring and summer months and at the mid-point of the day. When healthy, a heart can be fiery with passion and purpose. Like these blossoms, the heart helps us to shine our purpose out into the world, fragrancing everything around us and gifting the metaphorical bees and butterflies with nectar.

There is something about being here in Nepal that makes my heart blossom. When I volunteered for the first time, I felt myself buoyed by the team of providers. I was able to communicate about cases and grow in a way that hadn’t been available to me in the US. The second time, I increased my leadership and teaching skills. I learned a lot of my strengths and weaknesses as a guide and was able to come back home and work on those. It propelled me into more teaching and mentoring and I found that I loved that work too.

This time around, I felt like my heart was overflowing with love for the Nepalese providers who run our clinic. I could follow the history of their time with us: starting as medical interpreters, moving to medical assistants and then going to Kathmandu to attend acupuncture school. Satya and Sushila both came to Tistung Bajrabarahi to make their home on the second floor above the clinic. Sanita also went to the acupuncture school and worked hard every day as a GoodHealth Nepal intern, learning under Sushila and Satya’s mentorship about how to provide the best primary care.

All three of these providers watch over the foreign volunteers, helping to improve their cultural awareness and train them in safe rural care. I was impressed with Satya’s ability to manage everything happening with the clinic, from creating a remote treatment center in Taukel and transporting foreign volunteers there three times a week to caring for the garden and fixing a roof leak. Sushila watched over the clinic operations every day, helping volunteers with their treatment strategies and orthopedic needling. One day, Sanita and I walked the five kilometers to the remote clinic in Taukel and I sat with her as she treated patients. She took a thorough history and was skilled with the orthopedic knee examination and treatment she had learned through ARP classes with Andrew Schlabach.

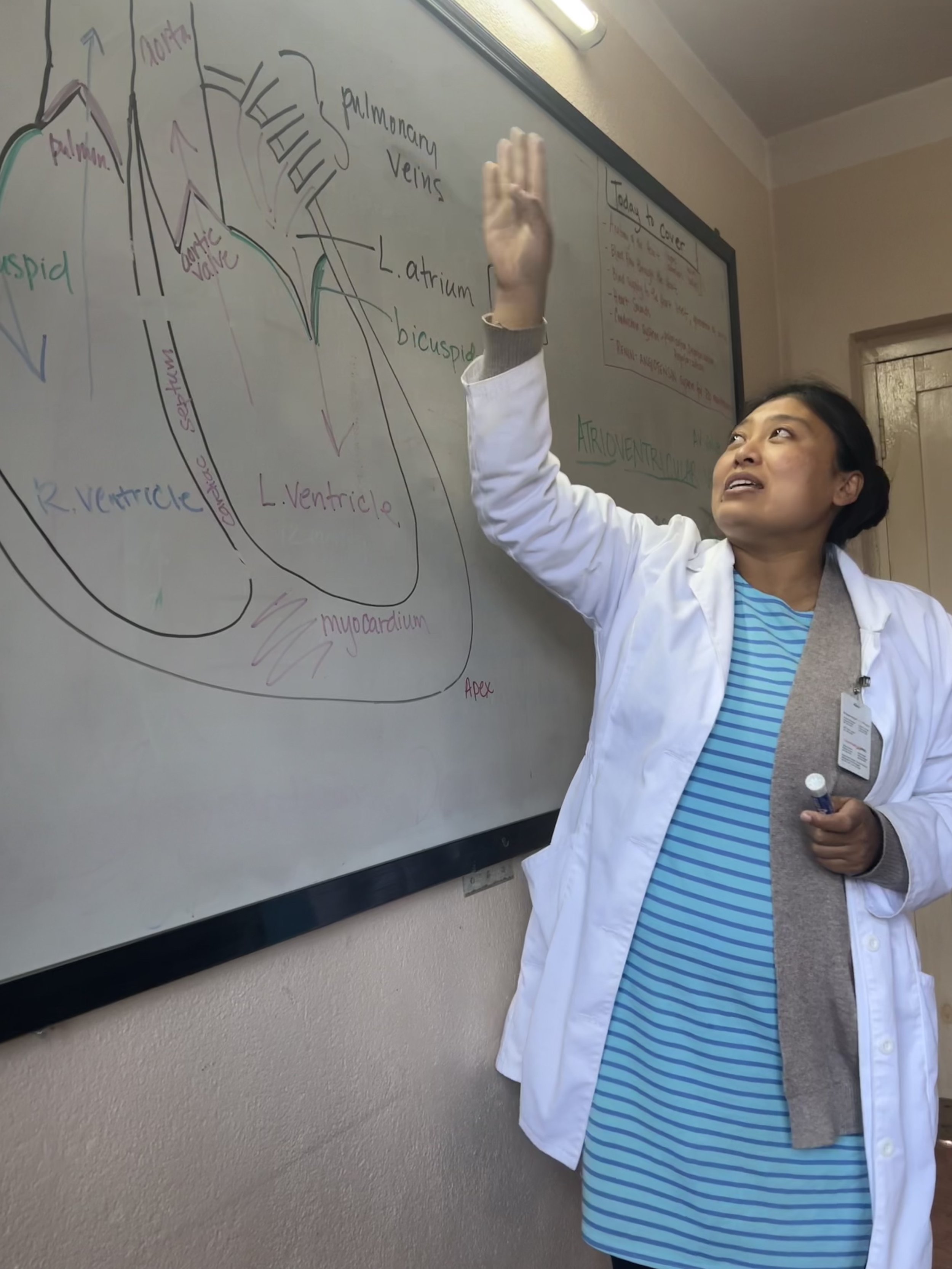

It was an incredible blessing for me to open the classroom in the evenings and create a space for learning with these folks. We started with a review of the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, weaving through endothelium, elastin, and collagen. We followed the spiraling flow of blood through the aorta out to the capillary bed. We considered how osmosis and differences in pH work their magic by perfusing nutrients and oxygen through the tissue beds. We covered the renin-angiotensin system and found it correlated with the seasonal flow in the Chinese medicine organs. Our classroom adventures took us to the cardiac pacemaker and the cellular membranes of cardiomyocytes. We saw the role that electrolytes play in the depolarization and repolarization that create the contraction of the cardiac muscle. Each step along the way, I stood aside for a moment while Sushila took over, reteaching each part of the lesson in Nepali.

By the second week, the foreign volunteers asked if they could join our classes and the Nepalese providers agreed. After clinic was over, we used the treatment beds to palpate the aortic diameter and inspected everybody for radio-femoral delay. With many colors, we drew out a theory that detailed how hypertension can cause atherosclerosis and we created charts of normal lab values. We were covering a lot and the work was so rewarding that I called home and extended my trip by two weeks. I would be staying until April 25th.

One day, I watched over the clinic with Sushila. After the foreign volunteers were done, I grabbed the stack of 50+ charts from patients they had seen that day. I audited them, invited the foreign practitioners to participate and put together a few extra classes to address some of the areas where I saw we could use some review. Abby Wollman (USA) and Marleen Timmers (Netherlands) showed up for all the sessions. Every morning, I was happy to see these two with their stack of yellow charts at the breakfast table. They talked with each other, dove into the Merck Manual and PubMed, and created differential diagnoses that they could use to get input from Sushila, Satya, or me.

In the weeks I was in Nepal, I woke before breakfast and either ran laps around the buffalo-grazing-volleyball field or did sun salutation series in my room. Sometimes we had dance parties after lunch. I taught yoga classes to anyone who could join at three or four o’clock. We laughed while we played Yaniv or Bug Your Neighbor with cards after dinner. We talked about the importance of exercise, meditation, and laughter for heart health, our own self-cultivation and modeling healthy habits for our patients.

I took on a few cases with Sushila and Satya. With Sushila, we provided team care for a twelve-year-old girl with severe cramping. She’d had the pain for seven months before her anxious father brought her to our clinic. She cried in front of Sushila and me as her left arm and hand visibly spasmed and her fingers contracted into a fist. She reported severe headaches and attention problems due to the pain and spasm. Her father had paid to see many doctors in Kathmandu, including two neurologists. They had run blood tests, a CT scan, and an MRI. Everything looked normal. They gave her a range of adult medications, including proton pump inhibitors, gabapentin, and nortryptyline. She continued to worsen. After three days with her chart, I was convinced she had a magnesium deficiency, but there was no magnesium available to give her. I worked to create a dietary regimen that would supply enough magnesium and gave her the nine electrolyte tablets left in my supply. Sushila treated her for liver blood deficiency with acupuncture and moxibustion and we used Guizhi Tang, as it was the only formula on hand with Shaoyao Gancao Tang in it. Within three days, she had no headaches and hardly any cramping. We showed her stretches and exercises to do at home and we tried to help her dad understand how to support her through any future growing pains with compassion, diet, and exercise.

Satya and I visited a middle-aged patient every other day at her home. This was hard for us, as he had the remote clinic every other day and we had to squeeze these visits in before our classes. Her sister had asked us to come to their home, as this person could no longer walk on her own and could not feed herself. We let the family know that we could provide 5-10 treatments this way but if they helped, they would need to start transporting the patient to our clinic. Getting out of the house would be good for her heart and mind. Satya and I reviewed the charts together, which noted severe depression since the 2015 earthquake and a worsening of symptoms diagnosed as Parkinson’s. Satya would sing with her, sweetly urge her up and into the sunlight, support her to walk back and forth across the courtyard and shoo her relatives away with their spoons and cheer for her as she ate food on her own. Her family chose to continue her hypertensive medication but had stopped her levodopa during the pandemic. We could not convince them to restart her Parkinson’s prescription or get antidepressant medicine. Her depression was extreme and she preferred to lay in the dark on one of the four beds crammed into a tiny back room. Satya continued visits for a couple of weeks after I left, but the family was not willing or able to bring her into the clinic, get her to the hospital to re-evaluate her medications nor to the laboratory so that we could check her fasting glucose levels.

In the middle of April, I worked to create a class to cover some of the dyspepsia presentations the providers were seeing in the clinic. It needed some finishing touches, but I was tired and headed off to bed. I fell asleep as soon as my head hit the pillow. At midnight, I woke up to a phone call from the US. My stepson had died. I didn’t go back to sleep for the rest of the night. I knew that being far away in a family emergency was a risk I took when coming to Nepal. At 4 am, my younger children were home from school and I was able to call them to make sure they were alright. I didn’t tell them what had happened yet.

I packed my things and more tears came. I was filled with sorrow about my stepson mixed with the heavy grief I usually feel when I have to leave our clinic in Nepal. I tried to go to breakfast and go about my normal work the next day, but I could not make it through without crying. Instead, I worked at packing and rescheduling flights in my room and Sushila was kind enough to find me a ticket on a sumo into Kathmandu.

Leaving was nine days early and it was abrupt in a way I’ve never experienced. I had no time to say goodbye, but somehow Sushila and Satya had a cake made. After dinner that night, we smeared frosting on each other's faces and I managed to laugh between waves of grief. I would miss both of their birthdays the next week. I couldn’t think about that without tears. I wrapped their presents in hand-drawn paper and put some of my appreciation for each of them into clumsy words. My heart felt some sense of relief as I placed those packages on the table.

At 5:30 in the morning, I crept into the kitchen but Sushila was already awake with oat porridge and tea for me. I didn’t have any more tears left today, just my bags of things and a ticket for the sumo. I felt like a robot who was programmed to follow the planned course of events over the next few days.

Processing the meaning of this trip is something I usually start the last week before I leave. I spend a couple of days alone in Kathmandu to write and think about what happened. I didn’t get to do that this time. It’s been a month now. We’ve gone through the cremation, the memorial, the kitchen table covered with candles and flowers and cards, the food deliveries, and the research around how we talk to our younger children about suicide. I’ve slowly restarted at my clinic, though I’ve kept my weekends free for a while, to be with my family.

Did I do a good job in Nepal? Did it even make a difference that I was there? I can check the standard boxes around my teaching for anatomy and physiology, pathology, risk factors, red flags, and lifestyle changes. I must have done okay with these things because a few days before I left, Satya brought me a chart at breakfast. He told me the story of a 53-year-old man who came to the remote clinic with neck pain. He stopped the foreign provider before they treated the man with guasha scraping therapy. He had heard the pain started eight months ago after the use of a carotid Doppler. He decided to measure the blood pressure in both arms. He found a large discrepancy between the pressures on the left and right. He checked this again to verify. He knew that there was a risk of significant atherosclerosis or clotting blocking the blood flow, since pain like this can be a sign of oxygen-starved tissue. Because the pressure was lower in the right arm, he specifically worried about a section of blood vessel he could not remember the name of, the brachiocephalic artery. I was so proud of Satya for this. We sat down together and wrote a professional referral for the man to go to the only heart center that exists in Nepal.

I’m not sure if I can use words to identify what happened for me on this trip, especially not yet. It’s going to take some time for everything to settle, for the waves of the experience to ripple out into my life. I can say that my heart still feels broken, but in a good way. One half of my heart exists with the friends and students that I love in the Kathmandu Valley. The other part is here, woven into my family and community in the US. I am incredibly blessed that my heart gets to have two homes.

Verma N, Amresh G, Sahu PK, Rao ChV, Singh AP. Antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic activity of ethyl acetate fraction of Rhododendron arboreum Smith flowers in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats and its role in regulating carbohydrate metabolism. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(9):696-701. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60212-3

Baral S, Baral BK, Sharma P, Shrestha SL. Dried rhododendron flower ingestion presenting with bradycardia and hypotension: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16(1):189. Published 2022 May 13. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03413-8

Wrap Up Blog for the Acupuncture Relief Project